Cyber Security Assessors as Referees

Are we not like the credit ratings agencies? We are paid by a company to rate something they own or have created.

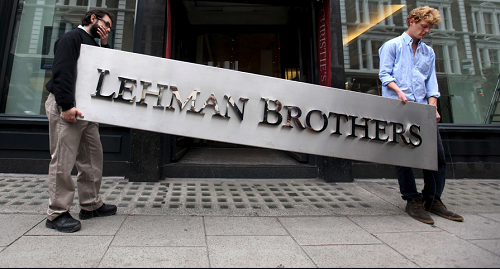

Michael Lewis had me wondering this after I listened to his podcast, Against the Rules. It takes a look at fairness and the role of referees in our lives, whether these are actual sports referees or language experts, fine art judges, or credit rating agencies. It struck me that those of us working in cybersecurity and compliance who perform penetration tests, SOC audits, and risk assessments could be seen as similar to credit rating agencies in many respects.

Similar Challenges and Dynamics

Conflicts of interest: We are supposed to be independent, giving our unbiased opinion on which others will base important decisions. We are also often paid by the people who own or operate the thing we are assessing.

Biases against bad news: Organizations, on any given day, would rather not get a harsh cybersecurity assessment report just as they do not want to hear their latest bond offering is not investment-grade. Even for a client that recognizes the importance of knowing the vulnerabilities in their systems, the cybersecurity assessor is adding problems to their plate that weren’t there yesterday (or they weren’t aware of yesterday), and this can have an unpleasant aspect to it.

Limited consequences: There is little to no liability for the assessor aside from potential reputational damage. I have never seen a case where a breach occurred and the firm that performed the security assessment (SOC2 audit, penetration test, or any other type) was taken to court and penalized. Similarly, credit rating agencies are rarely penalized for mis-rating a bond. Moody’s paid a rare $864M penalty in relation to the 2008 financial crisis, with no finding of a violation of law or admission of liability. This sounds like a lot of money until you consider that the U.S. Government Accountability Office estimated the cost of the crisis to be 22 trillion dollars.

Incomplete information: We security assessors don’t always get all the information we want, or all the information in the way that we want. We often must rely on the client to supply this information versus gathering all evidence ourselves from source. In the 2008 financial crisis, ratings agencies didn’t always get full visibility into the loan tapes (the list of underlying assets) for the bonds they were asked to rate. The presence of 3rd parties can exacerbate the problem as there is often less visibility into the 3rd parties an organization or system uses (similar to how some credit products, like CDOs, contain credit products from other issuers).

Attacker/defender asymmetry: I think of credit rating agencies as being on the blue team (the defenders). Malicious hackers (the red team) only need to find the one flaw in a system to exploit, while an assessor needs to uncover every flaw. Rating agency staff, as blue teamers, also need to find all the tricks that financial fraudsters (red team) may try.

What can we learn from the credit rating agencies to become better cybersecurity assessors?

How do we combat the inherent conflict of interest and other challenges? I could at least find some things that didn’t work for the credit markets.

One of the ideas from the SEC’s post-mortem of the 2008 financial crisis was to let ratings firms publish unsolicited ratings of bonds. The idea was that this would provide the market with additional views on a credit product’s rating that might draw attention to products that had been rated too highly due to the issuer-pay conflict of interest.

These would be unpaid, unsolicited ratings. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is little or no evidence of any solicited ratings being published. Not only do ratings agencies not want to do unpaid work, they don’t want to upset issuers by potentially lowering their credit ratings. The Wall Street Journal published in late 2019 that after a “thorough search” of its records, the SEC “did not locate or identify” any examples of unsolicited ratings published by ratings firms under the program.

Random assignment of ratings work was another idea but one that was never implemented. Thinking through these unsuccessful responses to the 2008 financial crisis led me to think about what the adjacent world of financial auditing might be able to teach us.

Any parallels or ideas from with financial auditors?

Some countries impose term limits for financial auditors to try to prevent the client-auditor relationship from becoming too cozy. This has been a controversial issue and has come in and out of regulations. Some of the main arguments against this rule has been that it can remove an auditor that has built up years of valuable experience, that it introduces additional switching costs, and that there are enough other safeguards in place to ensure audits are conducted properly.

Term limits are currently not in place in Canada (they were between 1923 and 1991) or the U.S. but can be found in some countries such as the U.K. (which has a 10-year term limit). More countries have a partner rotation rule that stipulates that the partner in charge of the audit must change every so many years (typically between five and seven years).

Term limits and personnel rotation strike me as a good areas to consider for a company’s cyber security assessors, many of which are the same firms that perform financial audits. Ensuring a company does not keep the same cybersecurity assessors year after year would ensure some fresh eyes are brought to a company’s security environment and can help prevent a too-comfortable relationship from developing.

Other ideas

Setting term limits would involve a company’s board of directors, and board leadership could support some other measures to improve companies’ cyber security.

Board members and a corporation’s investors should be informed whenever the company’s cyber security assessor changes, along with the reasons for the change. It can be an important event when a financial auditor recuses themselves or refuses to sign off on a company’s financial statements. Similarly, an unexpected change in a company’s SOC2 auditor may be an important sign of trouble.

Keeping separation between cybersecurity and other forms of audits could also be beneficial. Hiring a different firm for your penetration tests versus your financial audits, process certifications (e.g., ISO 9001), and similar assessment or audit activities can help prevent biases or conflicts of interest. In a softer form, an organization might require that non-financial audit services from the auditing firm must be approved by the corporation’s audit committee.

Conclusion

I find too often that assessors and auditors are portrayed as dull and plodding and no match for the super-clever hackers who are always one step ahead. I believe strongly that assessors and blue-teamers in general have the harder job because of the asymmetry discussed earlier – they have to watch for every vulnerability while an attacker just needs to find one.

Plus, red teams have the benefit of quick and consistent feedback. When your cyber exploit works, you know right away. When your defenses fail, you may not know for months (or years, or never). A lack of incidents may mean you’re doing a great job or simply that nobody has found your vulnerabilities yet (or they have, but you didn’t catch them).

Credit ratings analysts and cybersecurity assessors both deal with incomplete and ever-changing information. Their reports are not guaranteed to uncover all issues and should be components within an overall continuous risk management program. Thinking about the inherent limitations and potential conflicts within these activities and how to mitigate them can help in both accounting and cybersecurity.